- Home

- Leah Bassoff

Lost Girl Found Page 2

Lost Girl Found Read online

Page 2

When Mama returns from visiting relatives, buying soap and other goods, I cling to the backs of her legs as if in doing so I can pretend that I was there with her on her journey, magically hooked onto the backs of her sturdy calf muscles. I want to lick the mud right off these legs.

I am always with Mama when I can be, but sometimes I visit with my other mothers, too. Of all my mothers, Nakanoi is the toughest. She rarely has any food for us to eat and is only nice if my father is standing nearby. Natibol, another one of my mothers, is good to me. I like her large shoulder blades and the way her back is so straight when she carries firewood on her head. Also, she has a particular way of glancing over her shoulder at me when she dances that makes it seem like she is sharing a private joke.

Of all my mothers, though, my own mother is my favorite. This is not always the case with us. Some girls prefer other mothers to their own, but not me. Mama is the one who calls me by my special nickname, Chi Chi. She is the one who makes me laugh. She has a giggle that goes “Eee-heh-heh,” and she tells the most entertaining stories about animals who make the same mistakes that humans do, who are too vain like the flamingo or too gossipy like the square-lipped rhino.

My father is usually away traveling, visiting his other wives or pharmacies. But when he has a guest to entertain, he always brings him to Mama. My father knows that Mama is the daughter of a chief and knows the proper way to treat esteemed visitors. She knows which language to use — Latuka if they are from Torit, Taposa if they are from Kapoeta, Bari if they are from Juba, or Arabic if they are from Khartoum.

I watch how Mama acts around guests. She casts her eyes down, kneels to serve food, then disappears out of sight and commands me to do the same. Around the men, Mama is like a shy deer, but when it is just us girls, she turns back into a lioness.

Like all Didinga mothers, Mama beats me from time to time. It happens like this.

First, Mama lets me know she is angry with me for something I’ve done by giving me a look and a click of the tongue.

“Take care,” is all she says. “The next time it will be bad.”

In her head, Mama apparently keeps a running tally of how many offenses I have committed. She doesn’t share this with me until I have committed one too many.

At this time, Mama begins to list all my wrongdoings in order from first to last: “You see, in the past week you forgot your prayers, did not wipe your feet before entering the hut, then told two lies.” I nod and try to look ashamed, thinking this is the end of my punishment.

But later, when I come inside, I see it. Mama’s cane lying on the table. This means I am about to get a beating. Sure enough, Mama grabs one arm and slashes me with the other. I curl my toes as hard as I can to keep from crying. I don’t look into Mama’s eyes, not wanting to see the look of disappointment in them.

After she is done beating me, Mama gives me some tea with sugar. She does not hold a grudge. In her mind, the slate has been wiped clean, which means I can start in on new mischief.

Though I stay with her the most, Mama always tells me, “I’m your mother, but so are all these other women here.” What she means is that anyone can beat me if I misbehave. When it comes to us children, we can’t do anything bad without one of the adults noticing.

There are so many eyes watching me.

My cousin Keiji plays with me from time to time. She does not attend school like me. Instead, she spends much of her time fixing her hair or giggling over the local boys.

Though Mama does not approve of this behavior, rather than cane Keiji herself, she says, “I will leave it to God to punish this girl’s foolishness.”

When Keiji is no longer nearby, Mama tells me, “Some girls are like that, born silly.”

“And me?” I ask. “How was I born?”

“Fierce,” she replies.

Mama is always giving me advice.

“Treat the cows as well as you treat your family members.”

“Yes, Mama.”

“Stay away from puddles of water at night. This is where the mosquitoes gather. Daytime mosquitoes usually don’t cause problems, but evening mosquitoes carry diseases.”

“Yes, Mama.”

Sometimes Mama’s warnings are about health, but her other warning is more of a plea. “Do not become me,” she tells me, her voice turning low and raspy. “I never attended school, and now you must feel sorry for me. I never got an education, but you must. Otherwise you, too, will end up on your knees.”

———

I AM WALKING home one evening through the cool mist that always hovers around my village when I see one of my mother’s best friends, Chocho, hiding in some bushes.

“Auntie? What are you doing there?”

When Chocho emerges, her face is covered with wet leaves. She looks like some type of bush creature. I almost laugh, until I see the blood seeping out from under the leaves. Chocho doesn’t say a word, just turns away and walks towards her hut.

Later, I tell my mother what I saw.

“Her husband beats her, that is why,” Mama replies.

“Then why did she return to him?”

Mama looks at me as though I should know better.

“Where else would she go? If she leaves him, her family would have to return the cattle he gave them for a bride price.”

Without warning, Mama yanks my hair hard.

I cry out. “Why did you do that?”

“Let that be a warning. Stay in school. Never marry early or let your husband beat you.”

I want to protest that I am nothing like Chocho. The boys should be frightened of me, not the other way around. Rubbing my sore scalp, I decide it is best not to argue. I may not be afraid of boys, but Mama is another story.

Later that night, my older brother Lotiki starts in on me, teasing me about my dirty feet with that gruff low voice of his.

“Poni, Poni, not even a bath will clean you. You are muddy through and through.”

In response, I slap him hard across the face. His cheek reddens, while my hand tingles.

Abuba, my father’s mother, is staying with us. She sees what I did and hisses out a single word, “Kali.” Wicked. She then continues to give me an angry eye, even after I shrink away.

Abuba is right. I know I have a dangerous temper. Yet how can I explain to her how good that slap felt? How can I explain the thrill of it?

The next day I wake with sweat above my lip, my whole body hot as boiling soup.

Malaria. I know without being told. I try to curl my toes against the pain, which feels like bee stings up and down my body, but even this is too much effort. Instead I lie on my mat, letting Abuba’s declaration about my being wicked echo through my head. I am the one who has made myself sick. My temper has ignited the flint within me, and now I am filling with fire.

I hear my mother talking to Abuba in her hush-hush voice. “The fever is too high. Pray.” These are the last words I hear before I enter a dream in which burning grass scorches the backs of my legs.

Days pass, but I have no desire for food.

Mama makes a mixture of tree bark, groundnut shells and plant roots, a medicine my father taught her to make. Though he is a pharmacist, my father has always believed that traditional cures are best.

“Chew this,” Mama commands, sticking the paste under my nose. But I do not have the energy to talk or to chew. Mama grabs my bottom jaw with both of her hands and forces my teeth to move up and down. Then she clamps my mouth shut until I have no choice but to swallow. The taste is so, so bitter, but I cannot even make a sour face.

I fade in and out of sleep, but I am never comfortable. I am too hot, too weak. I am beginning to fade away, I think to myself.

Mama prays over me. “God, help Poni. Pour strength back into her.”

Even through my haze, I can feel the force with which Mama prays, the

way her body shakes. She squeezes the sides of my head with both her hands. Perhaps she is trying to squeeze the illness right out of me.

All I want to do is escape the heat of my body, to sleep, and yet something keeps pulling me back, back to my mother and her hands.

Every time I strain my eyes open, there it is, Mama’s face looming so large over my own.

In the end, Mama’s prayers are stronger than even the most bitter medicine, and gradually they work their magic. The heat slowly seeps out of my body, leaving me limp but calm.

It is only once she sees that the malaria is gone that Mama stops squeezing and shaking. She continues to sit on the edge of my mat. But now, rather than praying over me, she tells me stories.

My favorite is the one about the two brothers.

“An older brother always tries to beat his younger brother at everything. For a time, this works. The older brother is always able to run faster and climb higher than the younger one. But one day the younger brother decides to get his revenge.

“‘There is some fresh cow milk waiting at the top of that hill. Whoever gets to it first may drink it,’ he says.

“Of course the older brother wants to be the fastest, so he runs and reaches the top of the hill first. Sure enough, when he gets there he sees a puddle of white liquid. Feeling pleased with himself, he puts his mouth down and drinks it in one gulp. He doesn’t realize, until it is too late, that the white liquid is actually hyena dung. The younger brother is the one who has the last joke.”

I must be better now for, although I am still weak and my sides hurt, I start to laugh. It is the image of the boy drinking dung that does it, especially since I can imagine playing a similar trick on my own brothers.

As I continue to recover, I lie on my mat and watch Mama perform her tasks around the house, as if I am a baby seeing her for the first time. I watch the solid upper muscle of her arm as she mashes groundnuts and prepares sorghum. I watch her pulling a tiny pink thread through coarse white cloth, “needling,” the only time that she ever truly sits, as opposed to squatting when she is cooking or kneeling down when she serves my father his food.

I lie still and let Mama sing a lullaby to me, a song about a mother bringing her daughter fresh cow’s milk.

The skin above Mama’s nose crinkles when she smiles at me, and yet there are times when I catch her with her smile off, as if she has forgotten to put it on. At these times, she looks like torn cloth.

I know Mama’s biggest wish for me is that I follow a path different from her own, but at the same time, I want to sweep my house the way she does, always remembering to take the broom out of the hut and bang it against a tree to clean it off. I want my needling stitches to be tight and neat like hers. I want to cut vegetables as she does, so very thin, with the knife almost heading right into her thumb each time. Mostly I want to keep the faith the way she does, praying without fail two times a day.

My own prayers are rushed. I know I scatter my Blessed Gods about like careless stones, knowing that as soon as I have tossed enough of them, I may continue to play. Mama’s prayers are slow and deliberate, placed just so, like her stitches.

“You don’t take your prayers seriously, because life has been too good to you thus far,” Mama scolds.

I suppose it is true. Has life been good to you, Mama?

I know Mama carries with her a cloak of sadness, which she takes on and off. When she is around me and the other children, she slaps her knee and laughs. She lets me rest my face on the back of her neck and breathe in the smoky scent of her braided hair.

But with my father, Mama is different — quiet, head low, hand in front of her mouth. This despite the fact that my father has attended school and does not choose to beat her.

“Still, I never went to school, so I must kneel.” Mama shows me how rough her knees are. She makes me run my fingers across their crackly scars.

“Get an education. That way you will never have knees like mine. God saved you from malaria for a reason, Chi Chi.”

I nod. I am hoping Mama will bring me tea with sugar, then tell me more stories. Instead she kicks my mat and says in a stern voice, “Get up now. It is time to go back to school.”

“Go to school? Now? But I am still weak.” During my illness I had Mama all to myself. I do not wish to give this up.

But Mama has made up her mind. “You must return to school. You have wasted too much time with illness already.”

———

SEVERAL HARVESTS pass, and my brother Iko, who is one year older than me, turns fourteen. Mama must help him prepare for his initiation.

For this event, we make a huge bonfire. Iko has to jump over the fire while the elders give him thrashings with a black whip made of rhinoceros skin. Succeed, and he becomes a man. Fail, and he brings shame on our family.

Iko backs far away from the fire to get a running start.

“Jump!” I yell, so loud that the command cracks apart in my throat. Iko launches himself into the air with a holler. He clears the fire and lands on the ground with a thump. The elders sitting on the sidelines raise their gourds filled with home brew to show their approval.

Later, Iko lets me check his legs to see whether any of his leg hair got burnt off, but, no, it did not.

“You jumped so high,” I say.

After the initiation, we girls cover our bodies with white paint and do a special dance. Because Iko was successful, I sing, “Oh, look at my brother, how handsome he is. I can’t afford for someone to take my brother away.” All of us girls dance, stomping our feet and shaking the beads and bells we have fastened to our ankles. Some of the men play dried gourds or lokembe, an instrument they play with their thumbs.

We girls curl our stomachs in and out and sway our bodies to the rhythm of the drums. We tease the boys, too, getting close to them and then bumping them away. When we dance like this and sing our private female songs, I think of all of us girls as being one, as being so happy and free that not even the earth’s gravity can hold us down.

— 4 —

AFTER IKO’S INITIATION, we celebrate and dance. We eat goat meat and fresh blood drawn from the necks of cattle with miniature arrows.

The next morning I wake to a different type of blood.

“No, no. Not now.” I look down and see droplets of blood forming red petals on the dirt.

I am furious. My stomach hurting me was what woke me out of my sleep, and now, standing up, I see blood — my first monthly womanhood — spilling onto the dirt.

At age thirteen, I am just a year older than Nadai was when she got married.

There are so few girls who are allowed to attend school as it is. Of these girls, several disappear from school each month because they do not have sanitary napkins. Instead of going to school, they go to their huts for days, constantly having to wash the cloths they keep between their legs. There is no place to change the cloths at school, our only bathroom being a not-so-private latrine pit behind the school that most of us never use since there are so many flies.

Now I wonder what I should do. Mama enters and, once I tell her what has happened, she clicks her tongue, then goes and gets me a wad of spare cloth.

“You will not be a girl who misses school, not even for a day,” she insists.

“Fine,” I say with enough exasperation to let Mama know I am upset, but not enough to get me caned. It is not really Mama I am annoyed with. It is my own body.

I bundle the cloths Mama has given me as thickly as I can and stick them in my underwear. Then comes the walk to school, which I try to do without waddling like a duck.

As soon as I reach the classroom I sit down as quickly as I can and clamp my legs together, making sure the bloody cloths do not fall out. When the teacher asks us to stand and greet him, I do so with clenched legs. For the rest of the class I sit, thighs together, unmoving, legs going slowly nu

mb. I focus on what the teacher is telling us. Some seasons ago, I annoyed the teacher, and my punishment was to dig a hole for the trash behind the school. Today I make sure that I do exactly as he says, lest I get sent on such a mission.

Despite my annoyance, it is good that I am at school, because on this day the teacher shows us a big yellowed map with all of the different continents. The map is so old and worn that part of Asia is torn away, but China remains, and our teacher points it out to us.

“China, a country that is quite interested in possessing some of our oil,” he states. Our teacher is one of the few men I have ever seen wearing glasses, a gift from the missionaries. These glasses take up most of his face and make his eyes look huge. Also, he has a way of emphasizing each word when he speaks, as if each one is equally and extraordinarily important.

Next he points to the United Kingdom — “Home of the British who, along with Egypt, first colonized us.”

The teacher pauses when he gets to North America. “This is where most of the English in the world is spoken,” he explains. He tells us that the land in the United States is varied. Some of it mountainous, some of it flat as slate. Many different regions — north, south, east, west. He points to the Rocky Mountains in the western United States, “Tall like the Didinga Hills.” Then, as an aside, he adds, “I once met a Baptist American missionary from the land of Tennessee, and he told me that all Americans love something called pro wrestling. These men dress in gold and silver and capes, then fight one another.”

“Do they fight over land?” Tihou asks. She always asks good questions.

“I believe the wrestling matches are used to prove who is the most powerful.”

Our boys wrestle — it is one of their favorite pastimes — but dressing up in gold and silver? This sounds strange, but fascinating.

Finally, the school day is over. As I walk home, I can feel the weight of the blood-soaked rags I am carrying inside my skirt. I pass by the enormous baobab trees, many of their branches knotted like the limbs of elders. The trees themselves seem to say, “We, too, have to fight to keep our limbs from dragging to the ground.”

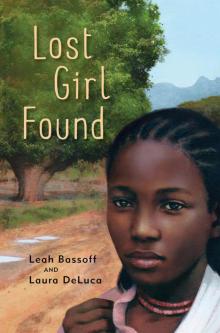

Lost Girl Found

Lost Girl Found