- Home

- Leah Bassoff

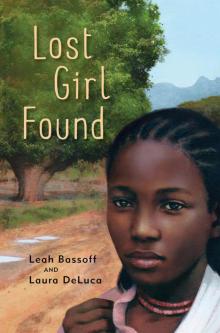

Lost Girl Found

Lost Girl Found Read online

Lost Girl Found

LEAH BASSOFF

and

LAURA DELUCA

Groundwood Books

House of Anansi Press

Toronto Berkeley

Copyright © 2014 by Leah Bassoff and Laura DeLuca

Published in Canada and the USA in 2014 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801, Toronto, Ontario M5V 2K4

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bassoff, Leah, author

Lost girl found / by Leah Bassoff and Laura DeLuca.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55498-416-9 (bound).—ISBN 978-1-55498-418-3 (html)

I. DeLuca, Laura, author II. Title.

PZ7.P295Lo 2014 j813’.6 C2013-905646-7

C2013-907144-X

Cover illustration by Enrique Moreiro

Maps by Scott MacNeill

Design by Michael Solomon

All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to Africare.org, a charitable organization that works with local populations to improve the quality of life for people in Africa.

To the young women who are the hope for peace in South Sudan

— 1 —

THAT ONE THERE? We call her Nadai. Nadai’s voice is as pure as a batis bird’s when she sings. Though she is three years older than me, she lets me climb up with her in the mango tree.

“Nadai,” I cry. “Let down your very long arms and pull me up.” And she does have the longest arms — thin but strong as rope.

“See how I can make the mango tree laugh,” Nadai says, and she shakes the branches, which makes several mangoes fall to the ground.

We eat the mangoes then — juice dripping down our chins — juice that Nadai wipes off with the inside of her wrist rather than her fingers. Nadai’s tongue is long, just like her arms. It makes me laugh.

It is Nadai who tells me things, Nadai who first shows me where the mouth of the mango is. Some mangoes have skin that grows yellow or pink on the outside, but here in Chukudum we grow Indian mangoes. Their skin remains green even when ripe. It is only by prying open the mouth of the mango that you can see inside.

“Poni, you are a hungry, hungry girl,” Nadai teases.

It is true. I can eat mangoes down to their last meaty string.

“Did you eat breakfast, Zenitra Lujana Paul Poni?”

Nadai’s legs dangle from the tree branch. She flaps her arms up and down as though she is a heron preparing to take flight.

“Mama fried a goat liver for me, and I ate it right up then ran all the way to school.”

“You run everywhere.”

This is the joke, my running. The women in my village entertain themselves by constantly sending me on errands. “Run and fetch some water,” they tell me, and then they laugh to see me sprint off like my heels are on fire.

“Why walk when you can run?” I say.

We stay up in the tree for hours. Below us, we hear the clackity-clack of children dropping round stones into holes in rows as they play mancala.

Another group of boys play football using a dried lemon for a ball. If they are lucky, one of the women will needlepoint a ball out of an old sock, since the lemons often split apart. When the boys score a goal, we throw the dark leaves of the mango tree up in the air to celebrate.

I like watching these boys. In particular, I like the way the goalkeeper stands, swaying back and forth, his eyes watchful.

So that you should know the truth about me, I am not only known as a runner but also as a troublemaker. Perhaps this is why I like Nadai. Like me, she is always eager to go to the forbidden river. “Kinyeti River, Kinyeti River.” We say it only in whispers.

Kinyeti River is where everything happens — where the women go to bathe, wash clothes, scrub dishes and share news. Yet this river is greedy. It eats large numbers of children every year when its waters are high from the rainy season. Some adults call these children sacrifices.

And do not forget the crocodiles. These beasts mainly keep to themselves, but every once in a while, one will draw its wrinkly body out of the water — its eyes as still as stones — and, with a snap of its jaw, carry someone off.

Mama calls the river Disease Soup, since it is filled with nasty illnesses. My father has told us we may not go to Kinyeti, not ever.

Yet how can we stay away from a river that is so much fun?

Once there, my brothers, Iko and Lotiki, coax me knee-deep into the water.

“It’s not so deep,” they say. Then they push me in all the way.

I hear a swooshing noise as the water yanks me under. My ears pound, and my throat burns. I kick and thrash at the water, which is like a python squeezing the air out of me.

Finally, I fight my way out, coming to the water’s surface with a pop. I continue to paddle my feet and arms crazily as my brothers cheer.

“Now you’re swimming,” they yell. It is as simple as that.

Later, they say they wouldn’t have let me drown for too long, would have waded in and pulled me out eventually, but this is how children are taught to swim.

I hate the river yet want more of her.

I sneak away to the river whenever I can and, when I do, I decide that I want to be like those boys and girls who can swim with a mat made of reeds held high above their heads. If the mat hits the water, it falls apart, letting the others know you weren’t strong enough to make it across. I try a few times, but every time I can make it only part way to the bank before my mat floats away in soggy pieces.

Nadai finds another way to prove her bravery, jumping into the water from the bridge that sits so high above it. For a brief moment she is dancing through the air, her body that of a dark fish that has been thrust out of the water. She screams as she makes a loud slap that cracks open the surface of the water and sends her plunging down.

We play, all of us, for hours, but because I have swallowed so much river water, when it is time to go home my brothers beat me around the stomach until I vomit. They do not want my father learning about Kinyeti.

My father is a clever man, though, a highly respected chief and pharmacist. When we get home, he takes one look at our red eyes and the white mucus that is gathering in their corners.

“Did you go into Kinyeti?” he asks.

“No,” I lie. But then, as I am talking, I can’t help myself. I give a shivery sigh. It creeps up inside of me — the result of all the cold water I gulped and vomited.

This one teensy little sigh is enough to tip my father off.

“You went in,” he says, and this time it is no longer a question. Secretly, I am impressed with the way he is able to read me, the way he stares me down.

That night he canes me using a thick branch that he has carved smooth. Whack, whack. My whole body aches from the beating. It is awful, and it is worth it. I know that I will return to Kinyeti.

———

WE CHILDREN ARE constantly on the mov

e, roaming among the tukuls, our round huts with cone-shaped roofs. Most of our free time we spend outside, climbing trees and exploring. It is not that there are no chores. All of my mothers have me wash the dishes so that I can practice bending my back. They have me carry small loads of twigs on my head so that my neck will grow strong, strong enough for the day when I will carry an entire jerry can of water on my head, or a full load of firewood.

When Lodai Giovanni arrives one dry afternoon, all of the women start dancing and jumping. He has come to claim another wife. Because he is wealthy, it is assumed that no one will reject his offer of cattle, goats and blankets.

When he announces that he has chosen Nadai’s family, her many sisters start gossiping. They wonder which one of them will be married off. At this time, Nakidiche, Nadai’s mother, is far away, gathering firewood. It is no matter, since marriage negotiations are done through the father and uncles. In fact, Nakidiche will not learn of her daughter’s marriage until the arrangements have already been made.

I see Lodai Giovanni walking towards Nadai’s hut. Giovanni is an Italian name, a gift from the Catholic missionaries, added to his Didinga one. Despite the lovely name, he is not pleasing to the eye, with a big bald spot and his hair parted on either side as though the Israelites have passed right through it. He is highly respected in the village, but he is also a man in his forties, married with many children.

Lodai Giovanni points at Nadai.

She is only twelve, has just had her first month’s bleeding. I hear the women whispering to one another, “Used to be, during the time of peace, that men waited until the girls were older.”

Nadai does not look up. She continues playing by our favorite tree. It is only after her uncle puts his hands around her waist that she realizes what is happening. She wraps those long arms of hers around the tree trunk.

Nadai’s uncle says a few words to her. At first he talks gently, explaining that this is her duty, that this is the way her mother was married. When that does not work, he simply rips her off the tree.

She screams, “No, no, no,” as if she is being attacked by wild animals. “Father, how can this be?” I don’t know whether she is calling to her own father or God himself, but her cries mingle with the ululation, the hoots of the women in the village.

We children look on, watchful as hunters.

As Nadai’s uncle drags her past me, I notice the inside of her arms where the skin has been scraped off in her desperate attempt to hang onto the tree.

Suddenly, she catches my eye. I see her look. Do something, Poni.

But what can I do?

No time is wasted. The villagers slaughter a bull for the couple, rub perfumed oil onto Nadai’s skin, then take her into Lodai Giovanni’s hut. I picture Lodai Giovanni — his skin as old and tough as animal hide, his belly soft and low-hanging — and imagine Nadai having to lie down with him.

Women change once they get married. I have seen it happen. Overnight, Nadai is no longer a girl who can play in trees. She can no longer attend school. Instead, she remains with Lodai Giovanni’s other wives, has to serve him dinner, has to kneel down. The other wives teach her to compete for Lodai Giovanni’s attention. They teach her to obey. It is rumored that if a husband does not beat his wife, he does not love her. Some of the older wives say, “Is it true that your husband does not love you enough to pay you notice? To beat you?”

I rarely see Nadai after she is married. When I do, I poke out my tongue, hoping she will show me her long one. But she simply nods sadly and turns the other way.

I remember that look of accusation in her eyes when she was dragged away. Do something.

— 2 —

NADAI TRIES TO KILL herself three times. Twice she attempts to hang herself from a tree. The first time, the rope does not hold. The second time, she is discovered, taken down and beaten. The third time, she eats some purple poison berries, but all that does is make her ill.

I think she is too strong to die, that one.

Only eleven months after she is married, I hear screams like those of a wild dog coming from the birthing hut. One of the women tells me that it is Nadai giving birth. Women are not supposed to scream out during childbirth, but Nadai does not care.

But when I come back later, there is no noise coming from within. It is then that I see the midwife leaving. There is blood on her skirt.

She makes a circle with her thumb and first finger.

“The birth opening was too small,” she says. “There was too much blood.” She has such bony, narrow fingers. I can’t help wondering if this comes from having to reach inside so many women to pull those babies out. She shakes her head sadly back and forth.

“Nadai?”

“She and the baby died. The baby will be called Ikidak.” Ikidak is the name for all dead female babies.

I can’t believe it. Nadai, who climbed trees so easily, whose body refused to die even when she tried to take her own life, is dead? I imagine the baby, a wet lifeless pile lying next to her. I don’t want to see this picture in my head.

Pretty soon, around the village, I hear women wailing and sounding out the death cry.

For the Didinga, when we hear the news of a death in the family, all the relatives go and smash everything in the hut — break the pots, pour the grains and flour onto the floor.

I watch the way the undersides of Nadai’s mother’s arms tremble as she picks up a pot and hurls it down. Next Nakidiche picks up handfuls of grain and throws them onto the ground. The grain scatters and rolls like beads.

While no one is looking, I reach down and pick up a small shard from the shattered pot and put it in my pocket. Throughout the day I take this piece out and slowly drag it along my arm, wanting the sharp pain on my skin.

When I see Nakidiche a week later, I call to her.

“What?” She looks up at me, her eyes as slow and unseeing as a fish’s. It’s clear she does not know me at this moment. Then, after what seems like a long time, she finally takes me in.

“Ah, Poni. You were a good friend to Nadai.”

I want to say how much I miss her, how playing in the mango tree is not the same now, but I remain silent.

“I have many daughters, you see, but Nadai was special.” She pauses and wipes her eyes with the sleeve of her dress. The sigh that comes from her is big enough to rattle the ground. “Nadai was the one I sang a special morning song to. She was the one I let lick porridge straight out of the pot.” I picture Nadai, her long tongue, her look of mischief. “Now she is with God. The baby, too.”

I cannot explain it, but I am disgusted with Nakidiche. I hate the way she stands there, her shoulders limp as a cloth doll’s.

“Why didn’t you save her? Why did you let her marry that man?” By all rights Nakidiche should beat me for speaking to an adult in this manner, but she looks too worn.

“How could I, a woman, stop the marriage?”

There was nothing Nakidiche could have done. She was not even there when it took place. Still, I am angry at her.

“You should have tried harder,” I yell. In fact, it was me Nadai begged for help, me who watched her get dragged away. My insides ache, and my throat hurts. I have never yelled like this before, not at anyone, not even my brothers. Certainly my mother would never allow me to raise my voice to her.

Nakidiche pulls up her dress and grabs the soft pouch of her stomach. She shows this belly to me, shows me without using words that there was a time when Nadai inhabited this flesh of hers. Now all that remains of her daughter is this stretched-out skin — scars like claw marks across her belly.

I don’t want to view her horrible stomach. Instead I turn and run away.

Usually we children look forward to funerals. My brothers have been known to ask hopefully, “Anyone go to God this month?” Funerals mean a big celebration with lots of songs and food, and sometimes a goa

t or even a bull slaughtered for the occasion. It is said that funerals bring together even the worst enemies. We celebrate the person’s life as we mourn their death.

Nadai’s death, like all children’s deaths, is different, of course — completely lacking in joy.

Nadai should have fought harder. Had it been me, I would never have let go of the tree, no matter how hard my uncle pulled. I would have held on until my arms pulled off.

This is what I tell myself.

— 3 —

HOW MANY WIVES does my father have? Good question. My father has four official wives, yet we know he has more than this. My uncle says six, my mother says twelve. Naturally, he does not live with all of these wives. Some of them he just visits in neighboring villages.

Because we have a large family, there are always children at our compound. For a time I don’t even know which ones I am related to by direct blood. But my own mother, Mama Nahoyen, remembers each ancestor in our complex family. She is the one who knows the who and what of our family, the one who makes certain that, when a marriage is going to take place, a man does not accidentally end up marrying his sister.

To map out our kinship ties, my mother draws a series of imaginary lines in front of her, lines like strands of spiderweb.

“You see, this one is the brother of that one, and this one is aunt to that one,” she explains, stretching her fingers apart and holding them in front of her face. Our family is like a tough math problem, but Mama can figure out the answer by looking into her palms.

Despite the fact that I sneak off, I am supposed to be the trustworthy one of our family. I am only ten the first time Mama puts me in charge of the house while she goes into a neighboring village for a few days.

“You are the girl in charge now, so take care of your brothers.”

So I do. While Mama is gone, I take over some of her chores. I turn pumpkin into stew, grind grains, fetch water and feed my brothers. I grow accustomed to Mama’s comings and goings, but I still ache when she is gone.

Lost Girl Found

Lost Girl Found